On 5 April 2023, Meta implemented a new process designed to let some Facebook and Instagram users opt out of receiving targeted ads.

Meta’s opt-out process is the latest stage in a legal battle that began in 2018—on the day before the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into effect.

But does the opt-out process comply with the GDPR’s principles of lawfulness, fairness, and transparency? Or is Meta’s opt-out form deliberately designed to dissuade people from exercising their rights?

Meta’s ‘Legal Basis’ Battle: The Story So Far

EU data protection law requires companies to establish one of six “legal bases” for processing personal data. The relevant legal bases for this article are known as “legitimate interests”, “contract”, and “consent”.

Meta (which was then simply “Facebook”) previously relied on “consent” for targeting ads. Facebook and Instagram users were deemed to have consented to this activity when they signed up to use either service.

But the GDPR tightened up the EU’s concept of “consent”, and Meta was concerned that its consent mechanism did not meet the new definition. So, on the day the GDPR took effect, Meta switched its legal basis to “contract”.

Contract vs Consent

Under the GDPR, data controllers such as Meta can process a person’s personal data when doing so is “necessary” for performing obligations under a contract.

Meta argued that its terms of service constituted a contract between the company and its users—and that delivering behavioural advertising was an obligation under that contract.

Under this interpretation, Facebook and Instagram users were not providing consent to ad-targeting—they signed up to receive targeted ads, and Meta was required to deliver them.

But after a drawn-out legal battle with privacy campaigners and regulators, Meta was forced to reconsider.

European data protection authorities found that using people’s personal data for ad-targeting was not “necessary” for providing Facebook and Instagram services, and so Meta had to find a new legal basis.

Contract vs Legitimate Interests

On 5 April, Meta changed its EU terms of service. The company now said it was relying on a different legal basis for targeting ads: “legitimate interests”. The change does not apply to UK users.

The GDPR’s legal basis of “legitimate interests” is flexible, and can apply in many different situations. To rely on “legitimate interests”, a data controller has to show that:

- It is pursuing a legitimate purpose (something legal, fair, and beneficial to the company or a third party).

- Processing personal data is necessary to meet that purpose.

- The company’s interests outweigh the interests and rights of data subjects (the people whose personal data it is processing).

This is sometimes called the “balancing test”. The idea is that a controller can use personal data in its own interests, as long as the risks to people’s “rights and freedoms” (such as the right to privacy) are not unduly affected.

But there’s an important difference between “contract” and “legitimate interests”: It provides people with the “right to object”.

The Right to Object

People have several rights under the GDPR regarding how organisations process their personal data.

One of these rights is known as the “right to object”. Under the right to object, people can ask controllers to stop processing their personal data in a particular way.

But, with one exception (direct marketing), the right to object is not absolute. Even if a person exercises their right to object, a company can sometimes continue to process their personal data.

To refuse someone’s objection, a controller must show that it has a compelling legitimate grounds to continue processing the person’s data that outweigh any risks to the person’s rights.

Nonetheless, if you’re relying on your legitimate interests to process someone’s personal data, you must give that person the opportunity to object to your processing.

(NB: Whether Meta’s targeted ads should require an absolute right to object is currently being debated in the UK courts).

Meta’s Opt-Out Form

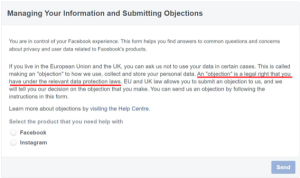

To meet its obligation under the “right to object”, Meta has implemented an opt-out form on Facebook and Instagram.

The GDPR’s principle of “lawfulness, fairness, and transparency” requires organisations to be reasonable and clear in how they communicate with people.

Controllers must also provide information about people’s rights in a “concise, transparent, intelligible, and easily accessible form”, using “clear and plain language”.

Adjusting other privacy controls on Meta’s platforms is relatively easy. Users can opt out of certain third-party advertising activities simply by toggling a button in their account settings.

Opting out of Meta’s core advertising services is much more complicated.

Step 1: Choose the Right Option

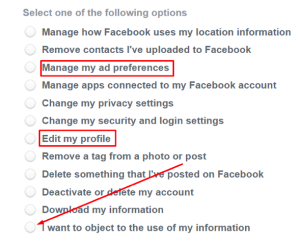

After a few preliminary questions about the user’s country of residence and the relevant platform (Facebook or Instagram), the form asks the user to choose one of 12 options.

These options are all privacy-related to some extent, and include “Manage my ad preferences”, and “Edit my profile”. Selecting most of these options takes the user back to Facebook’s “Help Centre” (the start of the process).

To opt out of ad-targeting, the user must select “I want to object to the use of my information”, which sits at the bottom of the list.

Step 2: Read the Legalese

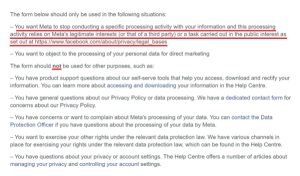

Once the user has selected “I want to object to the use of my information”, Meta presents some information about the right to object.

Using dense legal language could be seen as non-transparent and might deter people from exercising their rights.

Because the user wants to object to Meta’s ad-targeting, the correct option is the first one:

“You want Meta to stop conducting a specific processing activity with your information and this processing activity relies on Meta’s legitimate interests (or that of a third party) or a task carried out in the public interest…”

The Meta also lists five other purposes for which the user cannot use the form. This arguably adds further friction to the opt-out process.

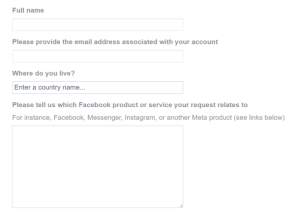

Step 3: Provide Information Meta Already Has

The next part of Meta’s opt-out form requests the user’s full name, email address, country of residence, and the platform to which their request relates.

Meta requested some of this information (country of residence, platform) moments earlier in the opt-out process. Meta already holds the other information (name, email address), and arguably does need to ask for it as the user is already logged into their Facebook account.

When a person submits a request under the GDPR, it’s important to verify their identity. However, the fact that a user is logged into a password-protected account should normally be enough to prove who they are.

Step 4. Explain the Objection

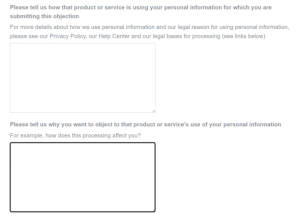

The next step in Meta’s opt-out process requires the user to explain why they are opting out.

Meta asks the user to explain “how the product or service is using (the user’s) personal information” and “why (they) want to object”.

For the average person, these are not simple questions.

Meta processes personal data in complex, technical ways that involve drawing inferences about people’s behaviour and communications, segmenting audiences according to their perceived interests, and selling the opportunity to target them with ads.

It’s not always obvious how such activity affects an individual user. Arguably, though, there are wider impacts to society when communications between over a billion people are commoditised in this way.

The tests set out in Meta’s opt-out form might deter some users from proceeding with their objection request.

Step 5. Submit the Form

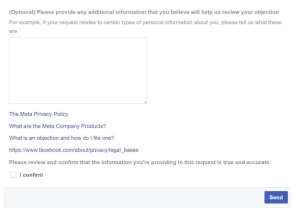

After providing the relevant information, the user can provide any additional relevant information and submit their request.

Transparency and Fairness

Meta was highly reluctant to change its legal basis from “contract” and is appealing the order that required the company to do so.

Providing users with the right to object might disrupt the company’s ability to effectively target ads. The company’s complex opt-out form might help mitigate this impact.

However, there are arguably issues with Meta’s process in relation to two key principles of data protection: transparency and fairness.

To grow sustainably, build trusting customer relationships, and avoid long legal battles with their users, businesses can make it easy for people to exercise control over the use of their personal data.

Simple and unintrusive cookie banners, accessible privacy notices, and easy-to-use data subject rights portals help people understand how businesses use their data and how to exercise their rights.

We hope this guide was helpful. Thank you for reading and we wish you the best of luck with improving your company’s privacy practices! Stay tuned for more helpful articles and tips about growing your business and earning trust through data-protection compliance. Test your company’s privacy practices, CLICK HERE to receive your instant privacy score now!